In Honor of June & Pursuit of Meaning

How Leighton's ultimate oeuvre "Flaming June" captures the pain and hope of an artistic calling.

Let me tell you a story about an exhibit that changed my life. Spoiler-not-spoiler: it’s bitter with a sweet ending. And it begins when I first met June at London’s Tate Britain in 2008. It was love at first sight.

I visited her again at Vienna’s Belvedere when she was on tour in 2010, and dragged my friends to see her while she came to stay at the Frick Museum in New York in 2015.

“I don’t know why I love this painting so much,” I confessed to the friends I brought with me, staring at the sweeping folds of her gown.

“Isn’t it obvious, Lesley? This painting has all your favorite things.” My friend went on to list them:

sleep

the color orange

Greco-Roman aesthetics

a beautiful woman

a body of water

symmetry

Put like that, it was rather obvious. We laughed. But in truth there isn’t a list of simple reasons that drew me to whichever museum June traveled to next. Flaming June impacted me in a way I couldn’t yet name, perhaps because I hadn’t yet named those parts of myself.

I know I’m not the only one who exists at the crossroads of multiple identities. I often feel like I’m forced to choose between Blackness and queerness, my American roots and my life in Berlin, the “arts” or the “sciences”. I honestly grappled with Flaming June for a decade, wondering why I was so drawn to painting of a white woman taking a nap. Is there internalized anti-Blackness I’ve not addressed? Or is it simply a genuine love of the female form…?

June dawned on me slowly. Mine is not a superficial appreciation for some pretty painting; I’m not a superficial person. Something deeper enticed me to London for a solo weekend in February 2017, when June returned to her birthplace for a stint at Leighton House Museum, the refurbished home of her creator housing the majority of his life’s work.

Flaming June was the last piece Frederic Leighton completed in 1895 before he died. He knew this painting would be the last he would share, and the knowledge of one’s approaching death is the context in which Leighton painted this vibrant affirmation of life. Flaming June is more than a symmetrically pleasing picture of a restful and orange-clad sleeper. It is an image that tells an aching story.

And that story begins with a queer artistic polyglot who never found a time nor a place to belong.

A Forbidden Expression

In the vein of Hannah Gadsby’s Nannette, I also believe it is pointless — verging on detrimental — to separate the artist from the artwork. Thus entering the Leighton House Museum, I would have to make my way through parlor, bedroom and dining room converted into galleries, ascend staircases of self portraits, and tread lightly upon creaking wooden floors where his studies and drafts covered the walls of the corridor. Only then would I reach the highest floor with the most light, the winter studio, where Flaming June awaited. In other words, to visit June I would first have to walk in Leighton footsteps, and learn all the creations that came before. I would join the artist with his art.

The receptionist explained it would take around forty-five minutes to see the entire museum, and three hours later, I came to know the shape of the artist who’d painted this profound bruise on my heart.

I dislike the term “gaydar,” like it’s some secret tool gay people have to sus each other out. It’s not. It’s simply harder for straight people to notice the signs because there are so few examples everyone is exposed to. For queer people, it’s easier to see the manners in others that speak to the manner within, often couched or downplayed for survival and/or passing. My “gaydar” is what I’ve learned over a childhood and adolescence of self-repression and self-delusion: when denied authentic expression, the self emerges in piecemeal patterns of longing in every other area of one’s life.

I walked through the remains of Leighton’s life, and I felt the self as I used to be. Call it what you will; he left no journals, few letters, and little explanations of his work. To many historians, he was an eternal bachelor with a mysterious flair. To me, this man was quietly, achingly queer.

Leighton was from everywhere, fluent in 5 languages, and in love with classical antiquity and the Middle East. I appreciate so much how Leighton portrayed womanhood and femininity; all his paintings are love letters, and his detail to form and color celebrate female beauty. However, he does so in a way that broadcasts authenticity and intimacy instead of sexuality and desirability. Women are the subjects of his painting, not the objects within them.

Women are the subjects of his painting, not the objects within them.

As with June and countless others, the women are unaware of the painter’s gaze. When Leighton paints a scene, he is a part of an intimate moment instead of intruding on one. And when the woman in the painting does look outwards, as in “Twixt Hope and Fear”, she is visibly disturbed by the viewer’s gaze (a male gaze).

When he painted a female subject, she was never a specific woman, but rather a combination of beautiful people he’d met overlaid upon Dorothy Dene’s form as the model. Most of the paintings he made were of female subjects, only a handful of male ones, and of those, most were infants.

Frederic Leighton was an outsider among London society who never married and never had children. He only had a couple close friends whom he invited to stay, despite being a well known salon host at the time. Dene, his muse, was assumed to be his lover in the second half of his life, but in seventeen years they were never married and she never had a kid.

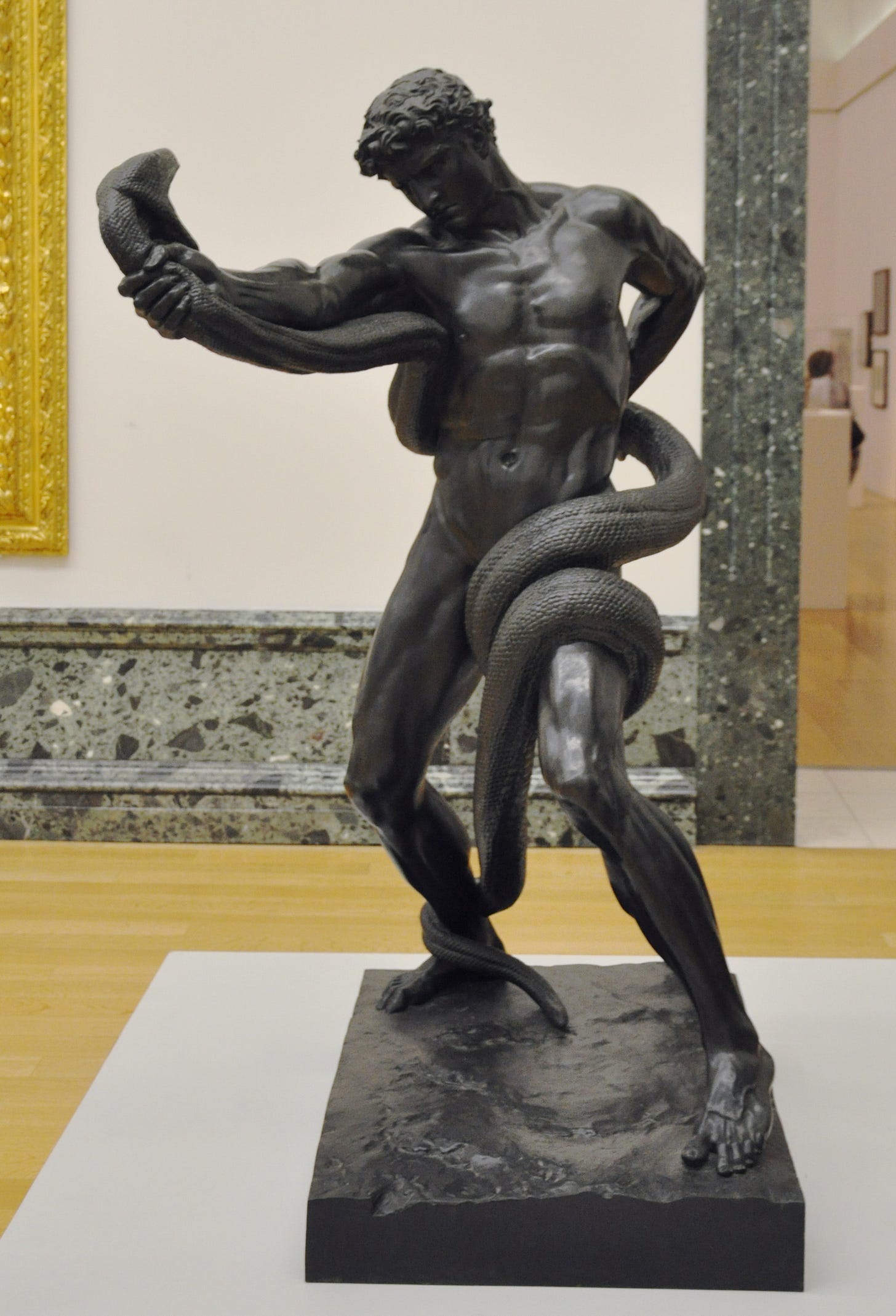

Furthermore when he did portray men, the result was strikingly, intricately sensual.

The Sluggard (1885)

I believed Leighton was queer, yes, but moreover that he loved women. Not in a carnal, sexualized way but in an open-eyed, open-hearted ‘I see you’ type of way. I like to think Leighton’s relationship with Dene was one of deep friendship: the kind of trust most women reserve for each other. To me, his female subject is a deeply queer expression of platonic love. He saw himself in her, and all the women he painted.

That day was the first time a painting moved me to tears. I don’t know how long I sat in Leighton’s studio before I managed to say goodbye to Flaming June in 2017. The sun did not shine the three days I was in London, but I didn’t miss it and nor did I need it. June radiated enough color from her heavy gilt frame to light up the dreariest of winter days.

How can I possibly explain the kinship I feel with this artist across time and space, class and gender, geography and medium? Flaming June is emblematic to me of the impact art can have on society. June is my personal talisman reminding me that art connects and outlives us all. That even if I’m writing a story no one truly understands, it will be understood by someone, somewhere, some day.

She’s hope.

A Beacon for the Future

I brought more friends to see her this past June at the Royal Academy, where she debuted into society in 1895. I walked into the gallery and thought, I love her even more today than I did when I was eighteen. I sat on the floor and began to write, of all things, a poem (and I am not a poet). This marks the fifth time I’ve gone to see June. One day I’ll make it to the Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico.

But on that day I asked my friends what they felt in the color palette, and whether she was asleep or dead, and if it mattered one way or another? Did they find her as beautiful as I did, or were her masculine features and prominently long thigh displeasing to their eyes? Did they sense the queer touch in strokes of Leighton’s brush…? How he invites us to contemplate femininity holistically instead of offering it up for cheap scintillation?

Such is the narrative impact of Flaming June. She’s the balance between vivacity and stillness. She’s the timeless moment between life and death. She embodies vast opposites and brings all the impossible beauty of a creative life’s end into one simple frame. June, like all true works of art, is as timeless as the human experience.

Flaming June is a tragic painting; she reflects my own pessimistic hope that refuses to give up on humanity despite everything we do wrong. June is my heart bursting with love for a world that erases queer Black bodies like mine. I love June for framing a visually harmonious contradiction: Flaming June is to smile through tears. It’s that joyfully vibrant song sung on death’s dark door. It is the pristine lotus flower blooming atop murky waters. It is that ironic belly laughter that bubbles up only when depression has dampened everything else.

She will be on view at the Royal Academy through January 12, 2025.

The contrapuntal poem I wrote for June is below. (Suggestion— read one indented stanza at a time, and then all together interspersed line-by-line.)

June Aflame That is the greatest gift of all to leave a legacy for the yearning unworthy June aflame in dreaming fantasy A truth captured by golden frame Cocooned in promise a question with no answer cloaked in sorrow could be the only peace there is. Her last breath, motionless and still alive the last words in a lost language in a bouquet of bursting color the last work of a hidden life Is she at peace? upon the wandering winds Sleeping now, she wonders whether loneliness is a burden, gazing through a window the sun rises or sets upon this island of dreams whether Hypnos remains by her side for an endless slumber or is she will slip into shadows and starlight among cascading orange hues of impossible loves Is this a dream, she asks? Have I awoken? Unspoken truth, faith unrequited Or was I never alive at all? Death is the spilling red of the waning sun's light June herself, a mirage of the soul and a perfect circle of belief Rest, now that hope is the chorus of this immortal farewell song Far-flung hopes born in secret necessity Dreams of tomorrow only to flower at death's door The will of a wounded heart never forgotten, never understood longing for color in this monochromatic life The mystery of the enternal question The slow withdrawal, a whisper "Am I alive?" Maybe only this, the act of dreaming

This is deeply moving and hopeful 💛

And your approach to art, the gaze in this text speaks more directly than many art historian’s approaches, because it is unburdened with the canon of how the artwork should be represented in formal text. This is such a touching, personal dialogue! I’m happy to see that the poem will be exhibited next to June.

Reading your text made my day nicer.

Looking forward to reading more of your writing!