Peace is a Lie... There is only Passion.

Why canceling The Acolyte weakens the Star Wars universe and the mythology of the Force.

Low viewership has apparently led Disney to cancel its best Star Wars series offering to date: the intelligently daring yet sadly short-lived show, The Acolyte. With The Acolyte canceled, Disney has effectively decided to squash any new hope of breathing life into the faltering Star Wars franchise.

I admit, unabashedly, that I love the Star Wars universe and I have for over two decades. And thus, I admit, loudly, my disappointment that corporate greed has prematurely ended any real investigation of the Jedi’s heretofore unquestioned moral high ground (…see what that I did there). But I continue this investigation, however. I have long questioned the Jedi’s heroics on the basis of one glaring omission from their creed: Love.

Star Wars creator George Lucas envisioned an order of celibate, knowledge-seeking warrior-monks to be the heroes of his timeless and hopeful story, one thematically rich in the deep emotion between friends and rivals, the love between parents and their children, and the loyalty between strangers uniting behind the common ideal of democratic cooperation. The villains of the story, ironically, are led astray by uncontrolled emotion; the heroes, nominally, abstain from emotion to defeat them. What an intriguing contradiction! This mismatch has bothered me for over half my life, during which I have been *waiting* for the Star Wars canon to address the role of love - be it familial, platonic, or romantic - in the mythology of the Force (may it be with you).

The Acolyte promised this and more as it took the main character, Osha, on a soul-searching journey to address the trauma of the violent event that orphaned her as a child and destroyed her home.

An Arbitrary Boundary Between Light and Dark

For casual fans who have never encountered the Sith Code, its first line is a perfect summation of the villainous ethos guiding every antagonist in the Star Wars films:

Peace is a Lie. There is only Passion.

The Acolyte is the story of how a young Jedi (the generally-accepted “good guys”) can be seduced by the Dark Side of the Force and become a Sith (the generally accepted “bad guys”). One need not investigate the villains’ raison d’être to enjoy all the starship adventures in the Star Wars universe. Arguably, this simplistic and binary worldview served “A New Hope” so well that this insatiably fun Space Western sold out theaters for months on end in 1977. But, when half a century has passed and this war in the stars has still not ended, one must indeed ask: what are they fighting about, anyway? Why should anyone care?

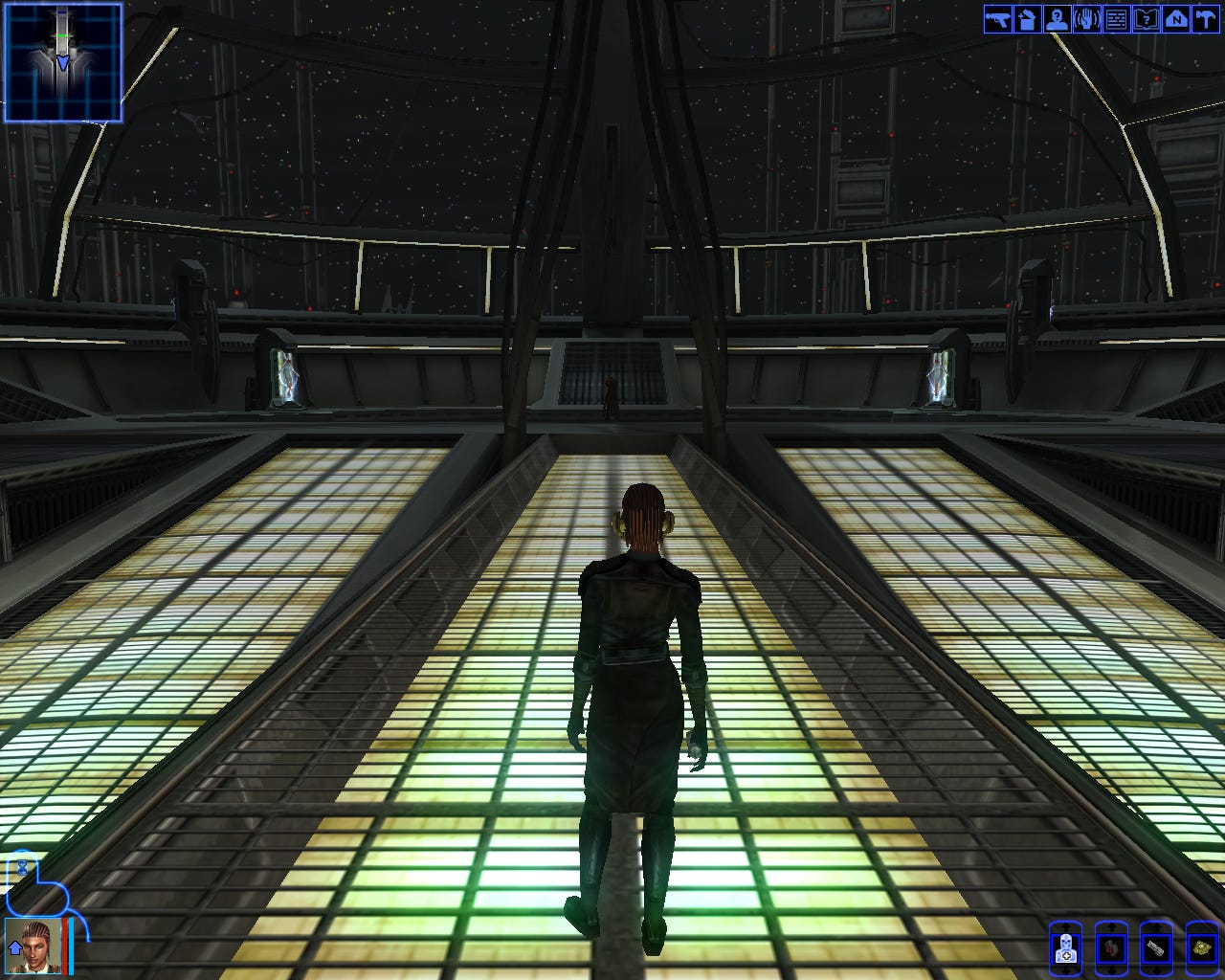

The Sith Code intrigues every Star Wars nerd who ever played the original “Knights of the Old Republic” (KOTOR) back on Xbox in 2003. As one such nerd, my year has been a whirlwind of heightened emotions revolving around the announcement and release of The Acolyte, the first series set in the Star Wars universe which is completely unrelated to the Skywalker saga or its various side characters. Without the constraints of near future or recently past events, the show could do what many other titles tiptoe around (if not blatantly ignore): investigating the cracked foundations of Star Wars’ morality system. By the Force, I was thrilled. The Acolyte promised to venture into emotional depths left unexplored in the Star Wars universe since KOTOR landed on shelves two decades ago. This whirlwind of excitement around The Acolyte has – for me and many other fans – ended in disappointment with the news of its cancellation.

Screenshot from the critically acclaimed 2003 role-playing action-adventure game “Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic.” Credit: Lucas Arts/BioWare.

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away… assumptions were made. Assumptions that goodness is unquestionable and evil is inherent. The six-episode arc of films detailing the rise, fall, and redemption of Anakin Skywalker has compelled generations of fans precisely because Anakin traverses the good-bad binary. Unthinkable! How could such a horrible villainous Sith have a heroic past with the Jedi? Is there still good inside him? Can Anakin’s son save him from his tragic, grief-stricken choices?

These are the questions that continue to draw audiences back to the original films. Sure, the starlit dogfights and hyperspace jumps, the Force powers and lightsaber duels, the futuristic-yet-analog computers and assortment of endearing nonverbal sidekicks all do their part in creating a marvelous universe. However, the emotional heart of these heroes’ journeys is one of loyalty to friends and believing in family, of nurturing one fragile hope for togetherness into a galaxy wide - well, - force. Star Wars gives us that elusive, intangible emotion enabling us to stand up against impossible odds because we know we’re not facing our struggles alone; because after watching Star Wars, this Force is with us, too. The narrative impact of this push-pull dynamic across the Light Side / Dark Side boundary is what led Star Wars to its timeless place of honor in societal imagination.

The Risk of Reviving Tropes

When Disney bought Star Wars, the franchise model promised a plethora of new films and spinoffs. While some of the new content is fantastic (my favorites include Rogue One, the final season of Clone Wars, and Obi-Wan Kenobi), I find most to be lackluster and quite a few titles utterly unwatchable. The variation in quality is not the problem. The problem is that the simplistic “good Jedi vs. bad Sith” morality cannot sustain the stories Disney churns out, betting desperately for one to become the next big hit. But isn’t it clear? There’s nothing more to wring out of this overwrought franchise without going back to basics.

Peace is a Lie.

It should be obvious, with a name like Star Wars, that any happy ending or peaceful resolution will be short-lived. But instead of regurgitating yet another Death Star, slapping new armor and names on what are clearly storm troopers, or raising an imperial mastermind from the grave, any new conflict should have arisen out of the arbitrary boundary of the Light Side and Dark Side of the Force, and those caught somewhere in between.

There is an inherent contradiction in peace-loving Jedi waging war, and war-hungry Sith making love. Because Jedi, for all their kumbaya togetherness, forbid personal attachments of any kind: no contact with one’s birth family, no investment in property or personal belongings, no romantic relationships, no bearing of children and certainly no raising them. The Jedi claim that desire for such attachments is a path to the Dark Side, and to evil.

So where exactly does love fit into the Star Wars mythos as it swells unacknowledged in the hearts of its characters, mysteriously guiding this sci-fi epic to such great heights?

Hot take — I’m not a fan of the Jedi. My love of the Star Wars universe began in 2003, playing the best RPG ever written, when I had to choose a side at the high-stakes climax of the story: am I a Jedi, or a Sith? The game “Knights of the Old Republic” abolishes the false binary of good vs bad in Star Wars. Both the Jedi and Sith have done unspeakable crimes in the wider galaxy and to the character herself (I always role play as a trans*woman in RPGs without a queer-friendly character creator). After 30+ hours of fantastic gameplay, my character was embroiled in a dilemma at the crux of the endgame: if morality is grey, what is the right choice? Does vengeance become righteous if forgiveness is impossible? I’m still haunted by the choice I made at the end of that game. And that’s how I came into the Star Wars fandom: criticizing the sanctimonious Jedi preachings, yelling at Yoda through the screen to stop with the whole “fear leads to suffering” nonsense, and silently urging Obi-Wan to just give Anakin a hug because his friend really needed one, you know? Also, the Jedi kidnap children to raise in their temples. Why does no one seem to have a problem with this? (“Because it’s tradition” doesn’t cut it for me…I want a show about Force-sensitive parents unleashing havoc on Coruscant to rescue their Younglings, please and thank you. But I digress.)

I cheered in The Acolyte when a character refers to the Jedi as “deranged monks.” Finally, someone said it! The Jedi have been coasting on the goodwill of the galaxy for far too long. The Galactic Republic fell to the evil Empire under the Jedi’s “benevolent” and “peacekeeping” authority. Surely, such morally grounded and powerful leaders should have stopped Sith Emperor Palpatine’s success. The fact that the Jedi Council played right into his hands is evidence of the rot at the core of the Jedi belief system. The animated series Star Wars: The Clone Wars examines these heroic failings to masterful effect, giving the franchise some of its most emotive and jaw-dropping narrative arcs (I’m looking at you, unforgettable Ahsoka. And Cad Bane the great. And the career badass, Assaj Ventress, who deserves her own series and also the world). Like KOTOR, the Clone Wars series examines that grey area between the Light Side and the Dark Side and in doing so, wins.

Freshly-helmed Darth Vader at the end of “Star Wars: The Clone Wars.” Credit: Disney.

Living, breathing, sentient beings can never truly divorce themselves from emotion, I think. Jealousy, self-interest, and hunger for power are just as present in the Force-sensitive population as in other groups in the galaxy, let alone the basic drive for emotional connection and conversely, the fear of abandonment. But the Jedi mantra? “There is no emotion, there is peace.” Call me Sith but as far as I’m concerned, the peace of the Jedi is a lie.

To ignore the ramifications of the Jedi’s self-denial is to rely on the tired tropes that have led us here, drowning in a stream of mediocre stories.

The Risk of Examining Old Tropes

How can Star Wars - a story about connectivity, hope, and familial love - entertain such a glaring hole in its ethos? Love is the redemptive force connecting Leia to Luke, Luke to Anakin, and Anakin to Obi-Wan. It’s how Jyn Erso succeeded in smuggling her father’s plans for the Death Star to the Rebel Alliance. (And it’s how R2D2 escapes every close shave to reunite with the heroes.) The Jedi Order has needed an update for thousands of years, because the Force they worship encourages a deep love for others that they simultaneously deny exists.

…There is only Passion.

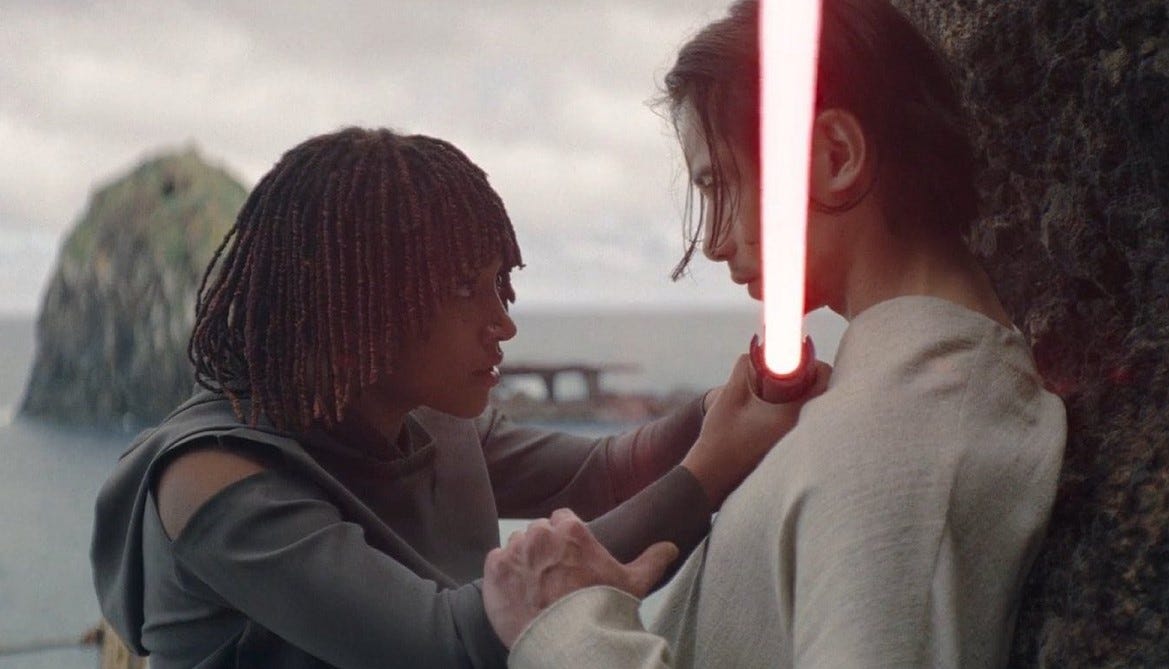

Here enter the Sith, proudly wearing their emotions on their sleeves. The Sith’s “rule of two”, the one the Stranger/Qimir seeks to follow in The Acolyte, is a relationship between mentor and student that evolves into an all-encompassing, sexually-coded partnership wherein one must eventually destroy the other. Qimir circles Osha like she is the perfect match: a potential lover whose hand he could swear and die by.

The Dark Side exists to challenge the Light Side just as the Light exists to illuminate the Dark. It is a brilliant, never-ending core loop of tension in which no side will ever vanquish the other. This is the essential war of Star Wars.

And ever-so-bravely, The Acolyte stepped into this moral quandary:

“I have accepted my darkness,” Qimir says to a self-hating Jedi. “What have you done with yours?”

He may as well be asking the Jedi Order, the audience, or hell, even Disney itself. He is clearly a villain and that cannot be denied (though I had to remind myself multiple times), but his seductive logic tapped into that loop of brilliant tension embedded in the mythology of the Force. He’s telling us that static platitudes are not enough, that the heroes are lying to themselves if they think all it takes is a flowing robe and a blue lightsaber to be a good person. To accusations of evil, Qimir replies, “Semantics.” (I died.)

When Qimir gives a name to the sparks flying across the screen, he validates the word, desire. Thinking back to Anakin, who was wrongly told his love for his wife and his need to protect his family were weak and shameful and would lead him to evil (cough cough — these same feelings ultimately save him and the galaxy), I rejoiced at this first canon-level introduction of emotion as a generative reservoir of Force powers. Qimir single-handedly embodies the central conflict of the Star Wars; major kudos to the casting director for finding an arresting talent and matching physique in Manny Jacinto, whose magnetic presence realigned every scene he entered. In appearance, deed, and thought, Qimir conducts that inevitable gravitational pull of the Dark Side, enticing us to accept our darkness, too.

Amandla Stenberg as Osha and Manny Jacinto as The Stranger/Qimir in “The Acolyte.” Credit: Disney.

Respectfully, Qimir’s tide pool exhibitionism achieved more for the Dark Side’s image than Darth Maul’s epic double light saber, more than Palpatine’s scary Force lightning, more than - dare I say - a sassy Vader disturbed by a lowly officer’s lack of faith. The writers and producers of The Acolyte pushed Star Wars to its (ethically hamstrung) limit and said: what now, fam? The question of whether or not Osha should follow a Sith master threatens the casual watcher rooting for comfortable Jedi “goodness”. Divisive, insightful and mesmerizing, The Acolyte sent a jolt sent across the Star Wars universe to reinvigorate its stagnant heart.

(Aside: I think this is more likely to happen when a racially diverse and queer-led team takes the reins. Jolts are uncomfortable to the status quo lulled into the complacency of the satisfied lowest common denominator. But looking back fifty years, was that not how “A New Hope” popularized the summer blockbuster, by jolting theatergoers into brand new frontiers?)

The Acolyte did this, perhaps, too well. And The Acolyte was canceled.

Is there hope in Disney’s Star Wars?

Others will and have criticized the show for its weak points. I recognize the uneven pacing was not ideal, and sadly this was not helped by the weekly release of episodes. There were one-dimensional side characters who died quickly and without consequence. To me though, these are fixable, superficial changes to production that future seasons could easily address. The core value The Acolyte brought to the universe was the richest addition since Ahsoka walked out of the Jedi Temple and Rex refused Order 66; the gift of the twins’ mutual sacrifice ached like Jyn Erso and Cassian Andor embracing on a beach; the meaning of Sol’s last words recalled the moment when a Jedi Knight of the Old Republic called Revan remembered her name with a weapon aimed at her forgotten pupil. Just like Anakin, Luke, and all these great characters before her, Osha faced an impossible choice, and, impossibly, she chose a side. The narrative impact of The Acolyte was so very worth investing in.

And for reasons I will never understand, Disney canceled this promising show. Canceled the potential for richer and more meaningful narratives while greenlighting fan-service mediocrity. The Acolyte could have improved over time if given a chance, but there’s nothing to be done to “fix” the hollow nostalgia-porn of Disney’s weaker additions to the universe. Its aimless sequel trilogy relies on over-orchestration to inspire emotion that the story fails to deliver. Fan-favorite characters like Han Solo and Boba Fett get pointless answers to questions no one asked. These series and films are bereft of feeling and collapse under the weight of their own special effects the moment nostalgia exits the chat.

Weak stories like the sequel trilogy can be well made. Weak stories can have great music, great acting, and great set design. Weak stories can be very entertaining, and even manage to make a profit! But the narrative impact of such stories is nonexistent. I have no intention of shaming fans for what they enjoy, just to call it what it is. We all have our preferences and biases, and we’re all entitled to our opinions.1 I call the sequel trilogy a weak addition within the framework of my narrative analysis and the decades-deep emotional arc Lucas has cultivated with his story.2 Standing on the shoulders of giants, these three films — The Force Awakens, The Last Jedi, and Rise of Skywalker — add little but superficial representation and flashy callbacks to the antics of the originals. In my opinion, “flashy” and “superficial” does not a lasting impact make.

A good story, on the other hand… A good story is timeless and will be retold for generations, and this, I expect, is why Disney bought Star Wars in the first place. Lucas’ Star Wars tells a damn good story. It is, effectively, a mythology of our modern era.

No one will tell the story of Episodes VII, VIII, and IX a generation from now (aside from future filmmakers learning from past mistakes). But I’m willing to bet The Acolyte will still be circulating among Star Wars fans as a cult hit, intriguing newcomers and challenging old hands, whispering the seductive Sith wisdom in the ear of its audience:

Peace is a lie. There is only passion.

And in a galaxy far, far away, this war in the stars will blaze to life again.

…Do you enjoy philosophical analyses of pop culture? Do you appreciate deep dives into narrative structure and mythological musings on the stories we read and watch, love and hate?

Then you’ll want to subscribe to Narrative Impact, a newsletter wherein I - a longstanding media consumer-critic, game writer, novelist and Physics M.S. - discuss the far-reaching effect of “a good story” through the exemplary lens of today’s media offerings. See my introductory post for more information. Thank you - and as always, just keep reading.

The author barefoot in a park with bubble (Germany, 2024).

I’ll be the first to tell you that my gaze is decidedly Black and joyfully queer. I will happily watch hours of trashy TV to witness melanated queers get a happy-ever-after, because that’s what I like. If what you like is to see the Millennium Falcon doing barrel rolls on your ultra high-def 4K screen, then by all means, go off, my friend.

See introductory post for my definition of “narrative impact”: